Hyper Attention Activity Deficit

I’ve renamed ADHD. I now think of this existence (note, I avoided the dreaded word, disorder) as HYPER ATTENTION ACTIVITY DEFICIT. I’ve been thinking about the term ADHD for a long time. It implies that the affected person cannot pay attention. But for a long time I’ve known that it means the person can pay attention to many things at once, thereby looking like (s)he is not paying attention to anything. Yes, of course, this can be a deficit for instance while driving, or doing anything rote – including taking a test on something you find boring. Sleeping can also be challenging as the ADHD mind tends to wander when at rest. But it isn’t that this mind cannot pay attention, this mind needs to think about a lot of things all at once.

This is why listening to loud music is such an effective strategy for “monkey minds” to get some sleep. They are forcing their minds away from all the things they want to think about and focusing on something they caused to overshadow everything else.

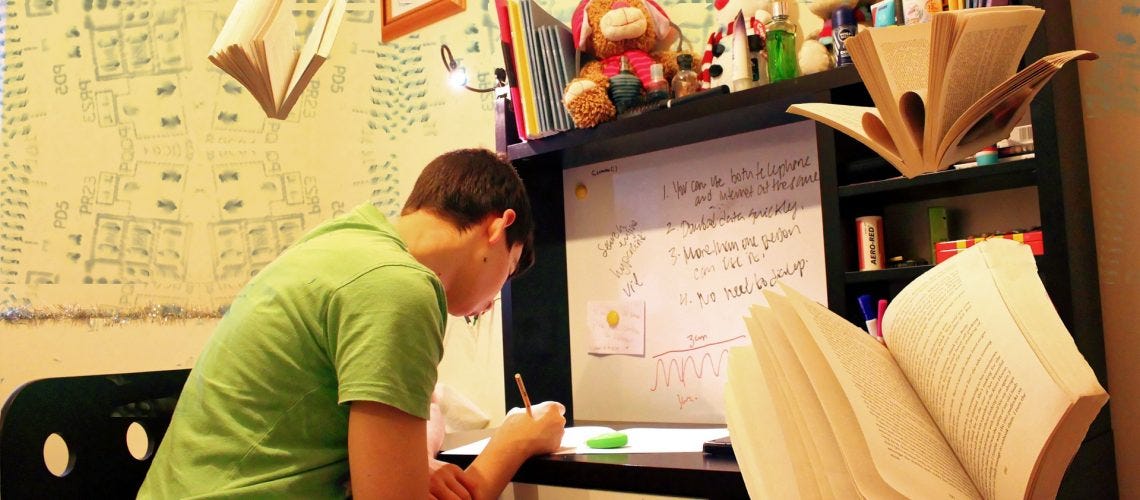

This is why doodling, pacing or even reading during class is an effective strategy for paying attention. I remember my son’s kindergarten teachers commenting that whenever someone observed their classroom they inevitably asked why the student who seemed to pay the least attention knew all the answers? My son walked around the room, played with legos, looked at books and then when the teachers would ask a question, his hand would shoot up and he’d have the correct answer. It’s when kids like these are forced to do only one thing that they are challenged to do anything.

It’s no wonder these kids who undergo neuropsychological testing are often diagnosed with slow processing speed and working memory issues. If the question, for instance, mentions that the character in a paragraph is wearing a red dress, the highly attuned – hyper attentive – mind may think, “hmmm, I wonder if the red dress is short sleeved or long sleeved? Is it warm enough for short sleeves? Is it a formal dress or casual? I wonder where she is going? I wonder if the dress is new? I’d like a red dress.” Clearly going down those rabbit holes will determine a slower processing speed. And with all those details running around in their brain, being able to hold on to the pertinent information and manipulate it, as working memory requires, can pose a challenge.

A client once shared that when her son visited a private school she received a phone call from the admissions director stating that he walked around the classroom looking at the posters on the wall. The admissions director labeled this “behavior” as disruptive and reported that the teacher was upset by it. The student, thankfully unaware of his “offensive” behavior, came home and excitedly began spewing facts and statistics he memorized from those posters. Of course it can be hard for others to concentrate while a fellow student is walking the perimeter of the classroom, but a simple appreciation and intervention – hand placed gently on the shoulder and a statement like – “Isn’t that information interesting Jonny? I can see how eager you are to read all the posters in our classroom. How about a few minutes before class ends I give you an opportunity to look at them and if you don’t finish you can come in at the end of the day and I’ll be happy to discuss them with you?” What an incredible opportunity that would have been for both of them. This child was able to pay attention to many things at the same time, which his peers were unable to do – in fact his presence on the perimeter of the classroom was keeping them (and the teacher) from being able to attend. Who has the attention deficit now? Bottom line, normalizing this distractible curiosity rather than shaming or reacting negatively, goes a long way in role modeling empathy and teaching acceptance of differences.

Hyperactivity; such a loaded term. How many adults wouldn’t give up a whole lot to have “excess energy?” These kids naturally have it. And again, like their ability to focus on many things at the same time, they can fire all sorts of psychomotor neurons indefinitely. This is a challenge if the world isn’t set up for their kinesthetic tendencies. But movement allows our brains to work more efficiently. Maybe that’s why these kids can do more than one thing at once. They are like their own personal brain generators. No wonder teachers are instituting creative “brain breaks” that include movement for their students.

So as I reflect on the challenges kids face who are bright and distractible, I can’t help but wonder why our society insists on changing these kids? Why not change the environment and encourage questioning, invigorating, thoughtful processes that these kids’ brains yearn to undergo. Flexibility, understanding, positive reframes and strength identification go a long way and must replace the assumptions, judgments and fixed mindsets of today’s classrooms and homes.

Hi Julie! I am a Learning Support Coordinator at a private elementary school for girls. I have read your book and many of your articles. This own hit home. I always consider myself an undiagnosed ADHDer. Your description of the reading process of someone with Hyper Attention fit me to a "T." I am one of those people who notice and take in everything all at once. I thought everyone did. Since I was a well-behaved little girl, my ADHD showed up in different ways. I tinkered and crafted and took bits of pieces of what I had seen and put it together in another way. In my role now, I created the Wonder Studio - where my students come for indoor recess to work on crafting projects of their choice. It's very messy and chaotic and they love it. Thank your this article. It made me feel less alone!

I love this and see myself in so many of your descriptions. Early school was okay because there was still some freedom to move around and desks weren’t front facing. The more the system required me to sit still and stare frontwards as I got older, the more I doodled the life out of my notebooks with increasingly complex drawings, sprawling mind maps and bits and pieces of thought (thankfully I was discreet enough to get away with it). I was always taking the lesson in while I did that but in assemblies, where I had no pen and was forced to keep every limb as still as possible, I would come away with absolutely no idea what they had just been talking about and it would feel cognitively stultifying.

At home I could study with a loud TV on, or I would get this urge to find new and slightly bizarre places to do homework. During one memorable phase I set up a desk in my parents’ hallway right against the front door, which my parents thought was so odd, but somehow the fresh environment in the hub of the house, with a different window to stare out where people actually passed by (unlike my room) helped my brain actually start. My quiet bedroom felt stifling during that era, when I needed to be able to take so much into my brain. In fact, a system that wanted me to sit still and keep to the same desk was challenging in ways I could have done without once the exam era started and I never worked like that again, once I had autonomy.

These days I shift around, walk around, stim, go off on tangents, pause what I’m doing (sometimes even my sleep in the the night) to crystallise thoughts into note form, and generally fidget as much as it takes to keep my brain online and fuelled with what it needs. Years of self-employment helped me build a life around that. But I also now realise that the one job in 40 years that really nailed me to a desk broke me. I used to think it was just stress, but I am starting to suspect enforced stillness was a bigger part of the burnout than I understood.